Perhaps the most important property of lube oil is its ability to remove heat from a surface where two or more metals are sliding across each other. In much the same way as air flows around cylinder head fins to remove heat, oil flows through a bearing and removes the heat caused by friction. I can’t imagine the destruction which would follow from assembling an engine completely dry.

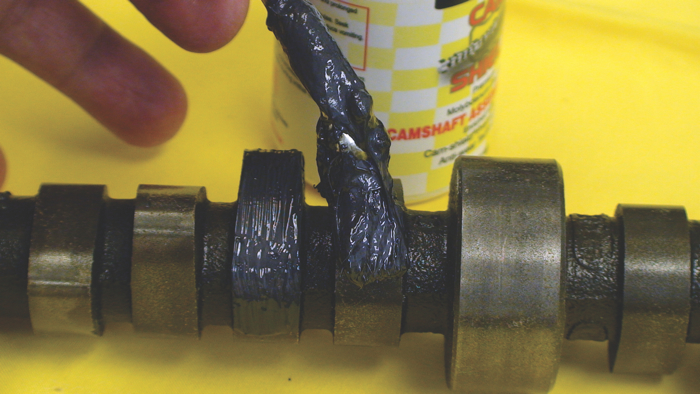

A thin coating of assembly lube should be applied on all high-friction, high-load surfaces including rod, main and cam bearings.

Assembly Lubes

Assembly lubes are one of the most important parts of an engine build. But, some components are hard to lubricate prior to start-up, and other parts allow assembly oils to drain off during storage. Let’s address the best way to overcome both of these problems.

Prior to learning about greases, I used a mixture of SAE 30 grade motor oil and STP on my engine builds. I put that very stiff goo on everything from rod and main bearings to pushrod tips. The engines I built using this technique were often very hard to turn over fast enough to start in the days before gear-reduction starters.

Then I learned to use my head for something other than a hat rack. Most engine builders (other than the fueler gang) pre-lube their engines by either pressurizing the oil galleys or spinning the oil pump until sufficient oil pressure is achieved. This means builders can use oils similar in viscosity to the oils they would actually operate their engines on. Hard engine turnover problem solved.

But what about those engine components not directly lubricated by engine oil pressure? Camshaft lobes, flat tappet lifters, and pushrod tips are lubricated only by splash after the engine is running. One can use oil to lubricate these parts prior to startup, but what about long-term storage?

Long-term storage can allow oil to run off these parts over time. But if we think about it, grease is merely a mixture of oil with what chemists would refer to as a soap substrate. Grease is designed to hold the oil in suspension until sufficient heat or motion builds up to release the oil and allow it to do its job. Grease is the perfect solution to stop run off.

From that day forward I’ve used high performance engine oil to lubricate all engine components except flat tappets, cam lobes and valve train components when assembling an engine. I even use oil on the cam bearings and journals, but on the cam lobes, flat tappet lifters and pushrod tips I use grease. You don’t have to use grease on cam lobes and roller lifters, because roller lifters don’t slide across the cam lobe. I’ve had zero failures since I learned to use grease.

Fueler racers use very heavy oil (60 or 70 grade), grease, or a newly developed gel on their engine components, because they just don’t have sufficient time between engine rebuilds in the pits. Besides, those hand-held starters deliver a lot more torque than smaller, gear-reduction starters.

However, I’ve learned something very important about which properties you must have in the grease you utilize. First, the grease must be oil soluble. If you use a grease like a white paste many people used years ago, you will find this material is not oil soluble, and you will plug oil filters with a white residue. That’s okay if you remember to change oil filters immediately after the engine is run for a few minutes, but I like things to be automatic so I don’t have to rely on my faulty memory.

Secondly, it’s a good idea to use extreme pressure (EP) grease, particularly when you have high lift cams and very stiff valve springs. Some greases just don’t have the film strength to protect components where the contact area is limited (like pushrod or valve tips). Even lifter contact takes place over an area much smaller than you would think. So I prefer to use EP grease all the time; it’s just cheap insurance.

Another area which needs to be addressed is the use of lubricants to properly torque head and rod bolts. Since this is a very involved discussion, I’ll save it for a subsequent article. There are some very important things to consider about torqueing bolts.

Some assembly lubes have a paste-like consistency and are applied with a brush while others are more like honey and can be applied from a squirt bottle.

Break – In Oils

I recall building an engine with chrome rings back in the ‘60s. I couldn’t get a decent break-in in spite of everything I did. I couldn’t figure it out, so I quit using chrome rings.

Then in the early ‘80s Daimler-Benz was using a very high-quality, high-TBN diesel engine oil as factory fill in all their engines to enable oil change intervals as high as 100,000 kilometers. They contacted us because these engines were burning excessive oil for many thousands of miles, and many customers were demanding expensive rebuilds prior to the warranty period expiring.

After considerable engine and field testing we discovered the high TBN diesel oil was preventing sufficient cylinder liner and piston ring wear to break the cylinders in. The harder piston rings, combined with the centrifugally cast alloyed cylinder liners and the excellent diesel oil had reduced wear to the point that some of these engines took over 50,000 miles to fully break in.

This is unacceptable, so we investigated the problem. We found that most wear in the piston ring/cylinder wall regime was caused by chemical corrosion, not lack of EP protection. But good EP protection was still necessary to prevent valve train failures during the break-in period. We then formulated a Daimler-Benz first-fill break-in oil, which had lower levels of detergency yet adequate ZDDP levels to protect valve train components. Problem solved.

Years later, I was talking with the head engine builder at Richard Childress Racing, and he stated that good, quick cylinder sealing was very important to his NASCAR engines. We drew upon our Daimler-Benz experience to formulate a low detergent, high ZDDP break-in oil for him to evaluate. Since automotive engine oils often contain friction modifiers, we also looked at the effect on break-in rate. Our resultant recommendation contained increased ZDDP, low levels of detergent, and no friction modifiers. The results were impressive, and he was very happy.

So what did we learn? It is imperative that the piston rings and cylinder walls quickly wear to the point that cylinder pressure leakage is minimal. Break-in oils can speed this process significantly over fully formulated automotive or racing engine oils.

This concept has been both dyno and field tested many times, and results have always been better than when using typical engine oils.

Conclusion

I keep a large container of break-in oil and a smaller container of EP grease in my shop at all times. Even though I once fired up an engine without an oil pump pressure relief valve installed, I’ve never suffered a failure due to lack of lubrication. The mixture of assembly lube and grease has always protected valuable engine components until the engine could be safely broken in.